Antarctic Forest

75 million years hence

75 million years in the future, Antarctica has moved north and collided with South America, forming a new landmass deemed Terranova. By now, the Antarctic ice sheets have completely melted, leaving it free to become a green continent once again. Now, it is covered by temperate-to-subtropical forests, largely composed of conifers that arrived from South America. This contact has also allowed native Antarctic fauna to mix with that of the now-isolated South America.

The ever-adaptable rodents are still prominent this far in the future, and fill many niches in the new Antarctic forest, from large herbivores to tree-climbing omnivores. A few adaptable primates can still be found in the trees, while snakes and lizards scurry about the underbrush. Flightless birds are also common on Terranova, including giant predatory petrels and many psittacoraptorans.

| Antarctomys | Antarctopsitta | Glutton | Hoplitotherium |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Click on a tab to learn more about that species.

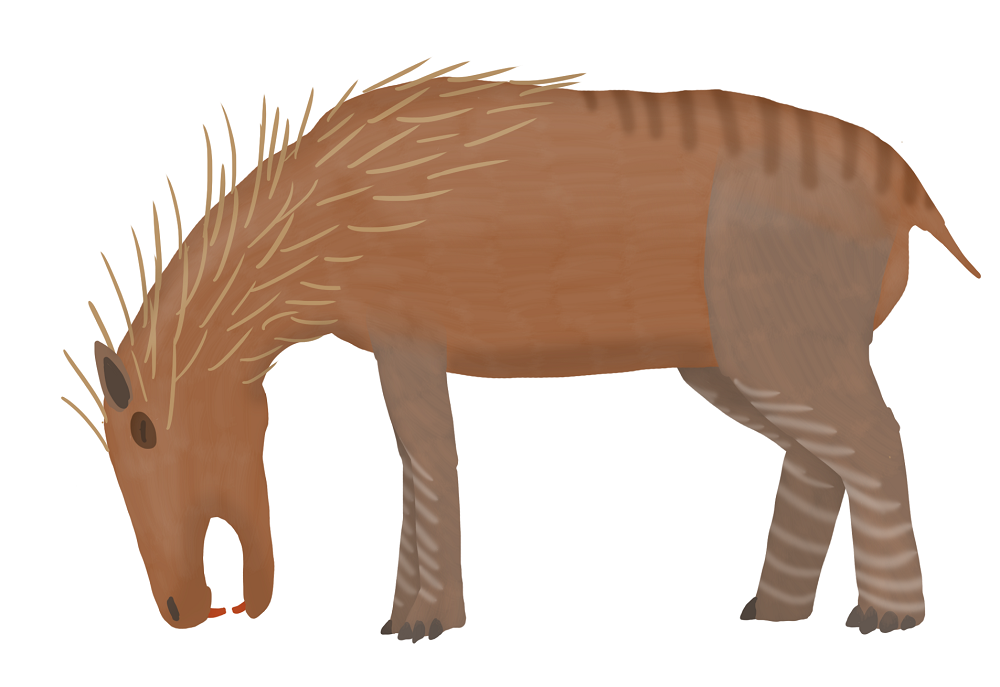

Antarctomys acanthocollumAlthough the highly adaptable rodents seemed poised for success after the disappearance of humans, they did not radiate as much as one might expect in the Epigene. The survival of many larger mammals such as ungulates, carnivorans, and primates constrained rodent sizes through the Cenozoic. After the Telogene-Tularean extinction, however, many niches formerly held by other mammal groups were vacated, allowing rodents to expand into larger body sizes. Antarctomys lives in South America and Antarctica 75 million years in the future. A herding animal, it grows to about 1.5 meters tall at the shoulder. The ever-growing incisor teeth of rodents have proven useful for chopping up grasses, leaves, and bark. Antarctomys evolved from a small South American rodent bearing protective quills, and a few of these quills remain on the neck, projecting more prominently from a shorter coat of fur. These quills can be effective for herd-based defense, but the limited quill distribution can leave lone individuals vulnerable to attacks from Antarctopsitta.

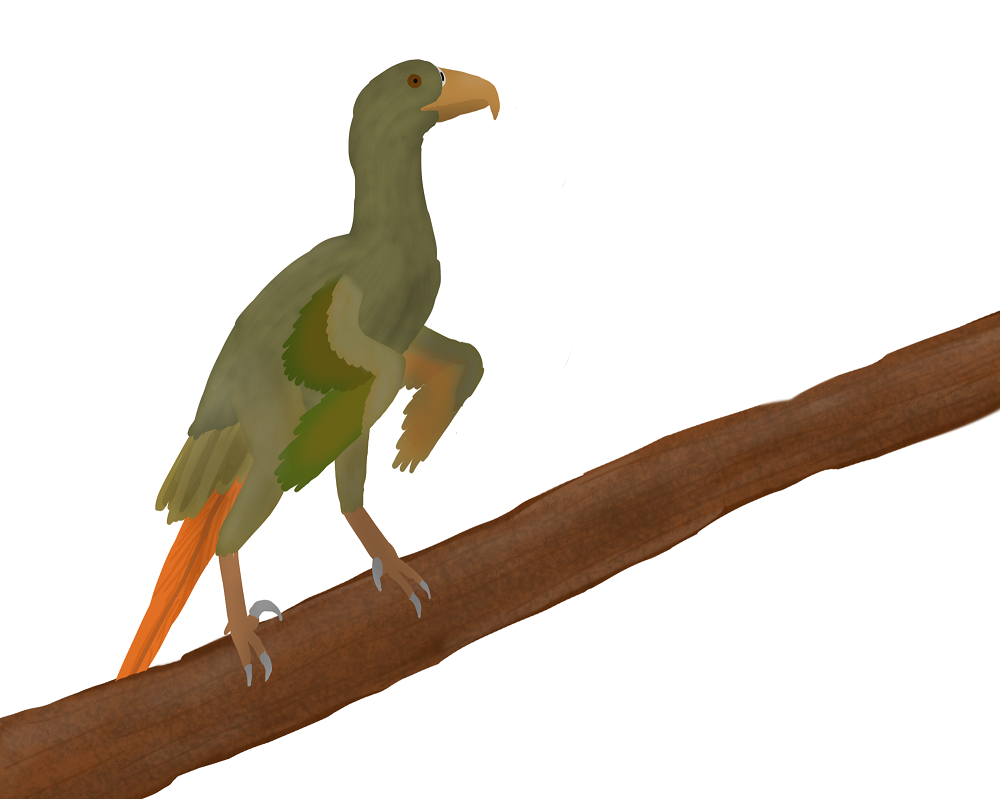

Antarctopsitta kirklandiAntarctopsitta is one of several psittacoraptorans that live in Antarctica. It is completely flightless, larger than the earlier Psittacoraptor and less fleet of foot. Antarctopsitta is intelligent and group-living; flocks of Antarctopsitta can number up to ten individuals, not counting nestbound offspring. Larger flocks can generally be found in more open areas, while smaller groups may populate denser areas in the forest. Antarctopsitta flocks may hunt larger prey in an organized manner, similar to modern gray wolves. This behavior is particularly effective against large herbivorous rodents such as Antarctomys. They have occasionally been noted to take advantage of the surrounding environment, even corralling prey into natural traps.

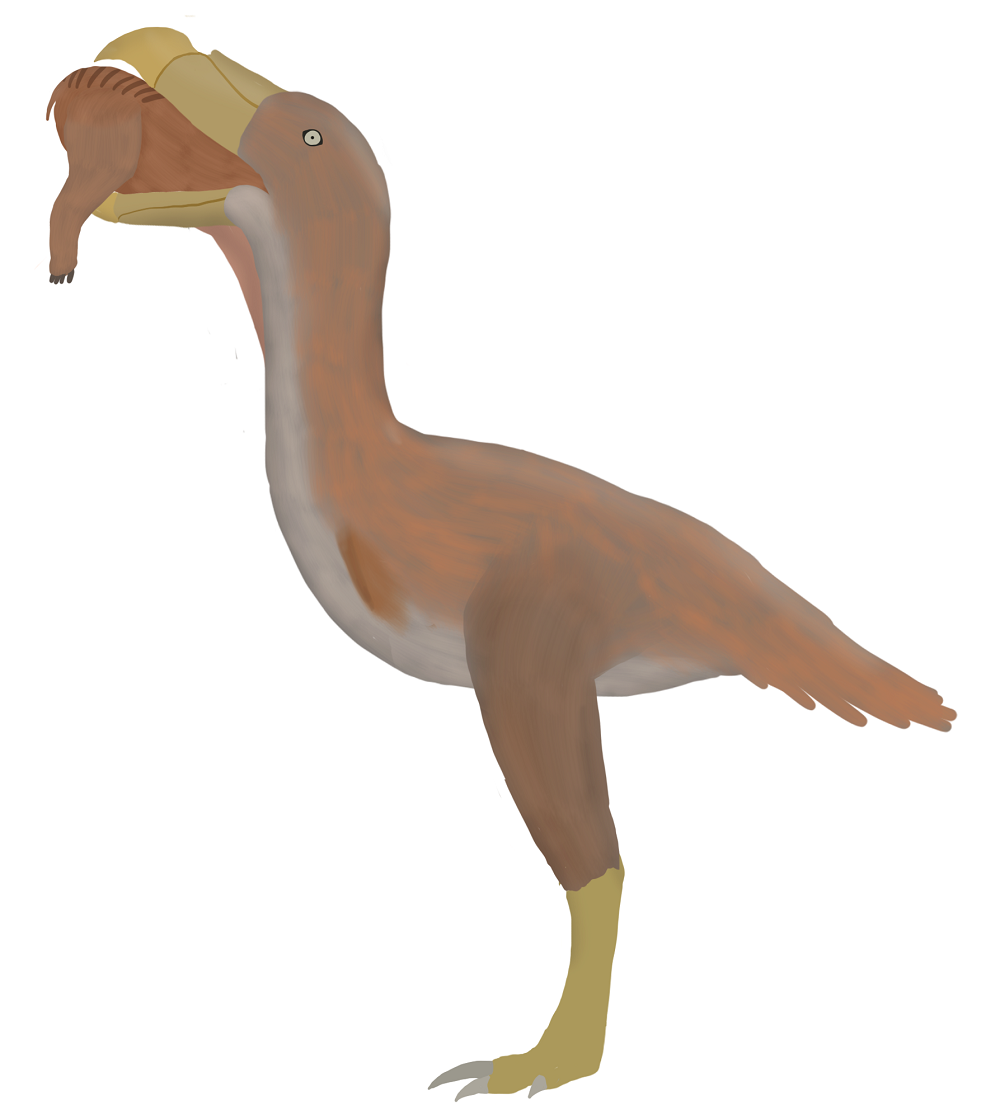

Glutornis gigasThe glutton is the largest predator of Tularian Antarctica. A descendant of the giant petrels, it is flightless and has highly atrophied wings. It is robustly built, with particularly sturdy bones in the neck and legs. Its skull is broad and bears a powerful, segmented beak. As with many procellariiform birds, its tube-shaped nostrils grant it a powerful sense of smell. Gluttons can grow up to 2.5 meters tall and weigh around 800 kg. The glutton is an ambush predator, using its beak and feet to dispatch prey. It has a habit of picking up prey in its jaws and slamming it on the ground or against nearby trees or rocks to kill it. Adaptations that formerly helped the skull withstand the pressures of diving now help it withstand the stress of this action. It will prey upon any animal it can kill, but prefers those small enough to pick up. Gluttons are solitary, with the exception of parents raising nestbound offspring - in this situation, one parent, which can be either the male or female, will guard the nest as the other hunts.

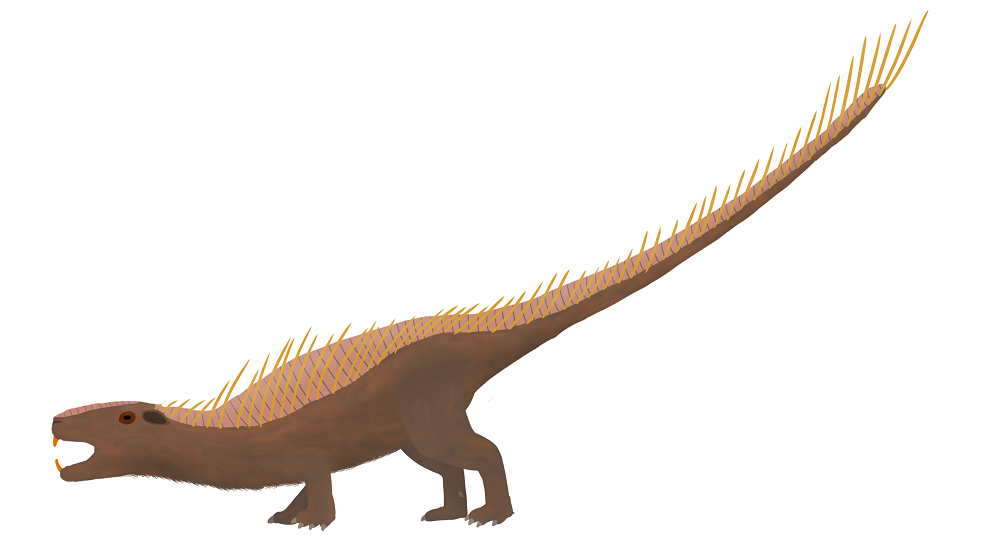

Hoplitotherium invictusHoplitotherium is a low-slung browsing herbivore that grows 1.5-2 meters in length on average. Much of its dorsal side is covered by hardened, overlapping scales. The scales are surrounded by a row of large, hardened spiny hairs on each side. These spines can be moved, allowing the rodent to angle them for defensive advantage. The spines continue down the tail, which is flexible enough to be used as a defensive weapon. These scales and spines offer Hoplitotherium an effective layer of defense against the predatory birds it lives alongside. Hoplitotherium shares a common ancestor with Antarctomys, both being descended from an armored rodent that survived the Telogene-Tularian extinction. Although Antarctomys and its relatives have lost most of their external defenses, hoplitotheriids have retained and expanded on these defenses. Originating in South America, hoplitotheriids become a globally-distributed group through the Proximozoic. |

| ← Central China, 62 myh | Thailand, 90 myh → |