Mediterranean Mountains

135 million years hence

Africa has been moving north ever since the Cenozoic. Shortly into the Epigene, the Strait of Gibraltar was closed, and the Mediterranean Sea dried out. The continued northward movement of the African Plate beneath southern Europe has raised the former sea, and through the later Cenozoic and early Proximozoic, uplifting has caused the formation of a mountain range starting around 45 myh. Now, the Mediterranean is one of the tallest mountain ranges in the world, with some peaks reaching five miles above sea level.

The lower slopes of the mountains bear montane forests, which give way to meadows further up the mountain. Rodents and lagomorphs graze these alpine prairies, and mountain dragons, enormous winged lizards, hunt them from above. Even further up the mountain, these prairies give way to barren alpine rock with sparse vegetation. Only the toughest organisms can thrive in this low-oxygen environment, such as insects, birds, denning dragons, and the hardiest of the herbivorous lagomorphs.

| Cystolepus | Montanalepus | Mountain dragon | Shovelhead |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Click on a tab to learn more about that species.

Montanalepus potteriSome lagomorphs have remained remarkably morphologically consistent for over 100 million years; apparently, whatever they’ve been doing has proven successful. Montanalepus can be found in certain portions of the Mediterranean Mountains, which by now. It stands about 75 cm (2.6 feet) tall at the shoulder. It is adapted for high altitudes, being more efficient at breathing and oxygen transfer than other jackalopes. Fur thickness varies between seasons and between populations living at different altitudes. Females and juveniles live in colonies, while males live solitary. Females have six to eight offspring per litter on average, and most of them do not survive to adulthood. Different species can be found in different areas of the mountain chain.

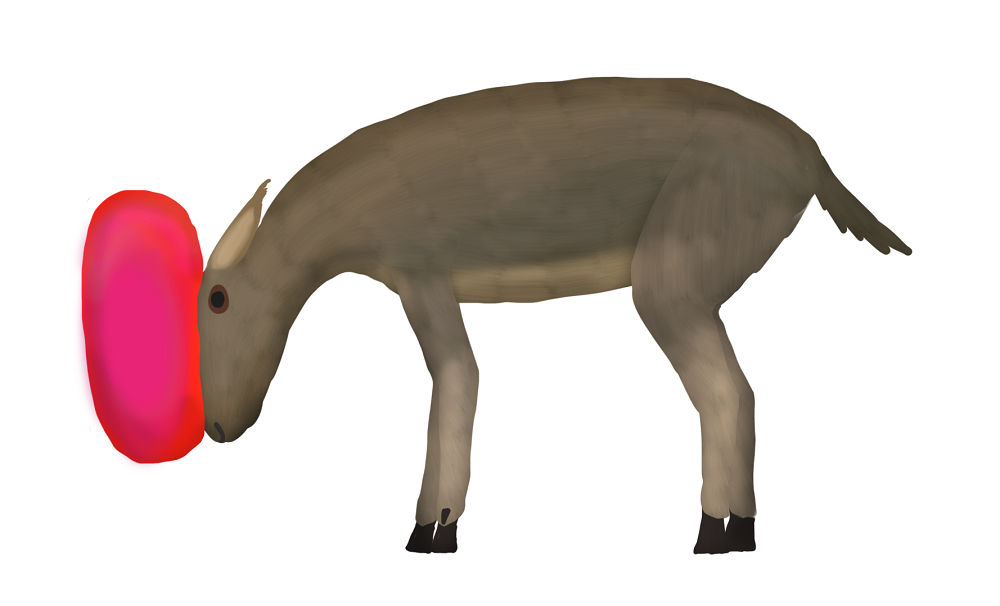

Cystolepus alpinusThe future has been kind to rabbits. By the middle of the Pluman period, they had evolved to take larger herbivorous niches multiple times. Notable radiations include in early Epigene Australia, late Epigene Eurasia, and early Tularean North America. Those descended from hares, such as Cystolepus, are properly known as jackalopes, and by the middle Pluman they are found almost globally. The Proximozoic jackalope lineage, which has a more cursorial bauplan, is divided into two main groups: those with “hooves” and those without. Hooved jackalopes do not walk on a singular ungual as horses do; rather, each “hoof” is formed by a fusion of the metacarpals/metatarsals and phalanges. Cystolepus lives at higher elevations of the Mediterranean Mountains than Montanalepus. It is smaller as well, averaging 55 cm at the shoulder. Its hooves are narrow and assist with climbing rocky surfaces. Cystolepus is most notable for the large inflatable sac at the top of its head. The sac is connected to the nasal passages and serves multiple functions: heating incoming air, visual display, and providing a resonating chamber for deep, loud nasal roars.

Italodraco giganteusMost species of dragon are restricted to the forests of Afroeurasia. In most open habitats such as deserts and savannas, birds hold the competitive advantage when it comes to volant niches. Mountains are different, though. Like birds and pterosaurs, dragons have evolved a unidirectional breathing system and a series of postcranial air sacs that help them breathe in a relatively low-oxygen environment. The adhesive pads on their hands and feet helped dragons literally get a foothold, and their large wings proved useful in absorbing solar radiation to help fuel their mesothermic metabolisms. The mountain dragon is the apex predator of the Mediterranean Mountains, with large individuals growing 7 meters in wingspan. Individual mountain dragons have large feeding ranges, often raising young higher in the mountains. Mountain dragons hunt on the wing and prey on pretty much any animal that they feel like eating. They bear semi-retractable foot talons which are often used to dispatch prey, but they seemingly prefer to startle prey into losing its footing and falling to its death.

Rutrocephalus armatusThis rodent’s genus name, approximately “shovelhead”, refers to two aspects of its anatomy. Firstly, the lower incisors, which grow straight anteriorly out of the lower jaw, and are used to dig small alpine plants out of the ground. A short, prehensile trunk helps bring plants into the mouth to be eaten. The upper and lower incisors are also used to produce sound, by rapidly and forcefully clacking them against each other. The name also refers to the spadelike shape of the plates around its head. These plates are movable and made of hardened keratin, similar to the scales of a pangolin. The usual shovelhead defensive strategy is to retreat into a burrow or among some rocks, facing outward with the plates closed around the head. It is very difficult for a predator to grasp or break the keratin plates. Shovelheads are noted to come in two color morphs, the significance of each is not very well-understood. |

| ← Thailand, 90 myh | Pacific Ocean, 175 myh → |