Open Pacific Ocean

175 million years hence

The Atlantic Ocean continued to widen up to the end of the Tularean. After that point, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge subducted, and the Atlantic's widening abruptly reversed. For the past 70 million years, it has been closing, and in turn the Pacific Ocean has become increasingly broad. The most distant stretches of the Pacific Ocean are now father from any body of land than any point of any ocean was in the time of humans.

Life thrives in these ocean seas. Plankton continue to form the basis of the marine food web, but numerous extinction events have changed the exact composition. The plankton are fed on by fish, which are in turn fed upon by squid, larger fish, fishing bats, fully marine rodents, and giant filter-feeding marine birds. The top predators of these open seas are large marine crocodiles.

| Cetornis | Cookiecutter squid | Dartsquid | Irwinbasileus | Sea orm | Seabat | Southern spear-toothed mermouse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Click on a tab to learn more about that species.

Pseudoeurhinus australisAll modern groups of marine mammals are extinct 175 million years in the future. By this time, new clades of marine organisms have evolved to fill the seas. Descended from common murids, the Nereomyoidea are nicknamed mermice. They have four paddlelike limbs and a flattened tail, used to swim with a dolphinlike vertical motion. Unusually for marine mammals, mermice are primarily visually-oriented creatures and retain color vision, fine-tuned to discern different shades underwater. The southern spear-toothed mermouse can be found in the southern portion of the now-widening Pacific Ocean. It grows around 4 meters in length, approximately the size of a dolphin. Although the cheek teeth are all conical and identical, mermice retain a distinct pair of incisors on each jaw. In different lineages, these may be specialized for different purposes. In the case of Pseudoeurhinus, the upper incisors project straight anteriorly from the snout. These incisors are used to corral, batter, and stun prey, similarly to the modern swordfish.

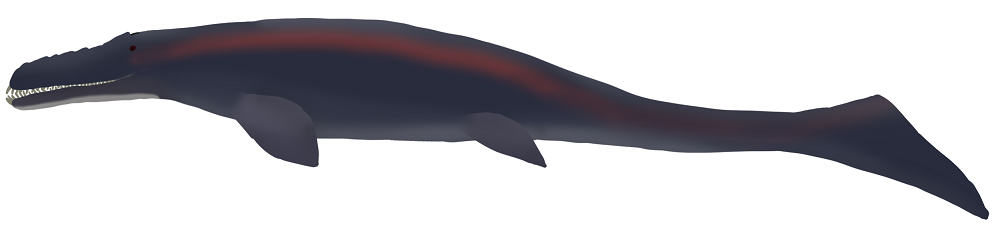

Irwinbasileus giganteusIrwinbasileus is one genus of large marine crocodilians common in the Pacific Ocean 175 million years hence. Even though it reaches 10 meters in length, it isn’t the largest animal in these seas. It has lost the thick armor of its ancestors, instead bearing smooth, hydrodynamic skin. Its diet consists of mermice, birds, seabats, large fish, and other crocodilians. Irwinbasileus still retains a degree of color vision, being able to tell different colors apart in seawater. Females are more prevalent in the population than males, and as such they face a degree of sexual selection. When ready to reproduce, females develop a prominent reddish stripe and produce loud calls which sound like a giant motor. These calls can carry for miles over the ocean, and serve to indicate their presence to both competitors and potential mates. Each individual has a distinct pattern to their call.

Cetornis dixoniAmong the largest birds to ever evolve, Cetornis can grow up to 13 meters in length. Cetornis is a filter-feeder, and bears large lamellae in the upper and lower beak to sieve prey from water. It completely lacks forelimbs and swims with propulsion from its large, paddle-like feet and tail. This swimming style involves staggered bursts of rapid movement, in which an individual can quickly consume a volume of water that may contain prey. Cetornis displays a form of “ovoviviparity”. Being too large to safely crawl onto land, it cannot lay eggs. Instead, the eggs are held inside the body until the young are ready to be born. The young are superprecocial and are born ready to live on their own (though they tend to stay near adults for protection). Juveniles preferentially prey upon zooplankton, while adults may also feed upon small fish or arthropods. The only known predator of adults is Irwinbasileus.

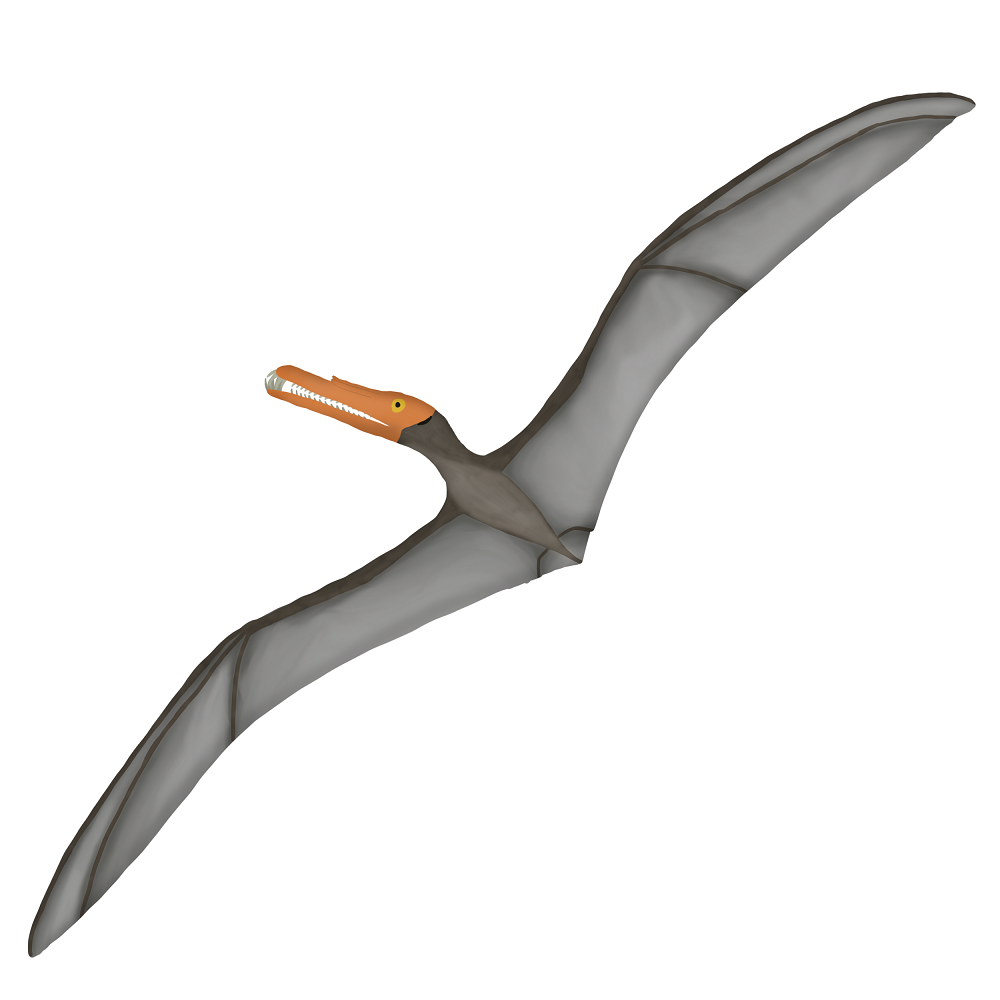

Halenycteris ekrixinaBats have had a storied history in the future. Being very diverse and populous, they survived the Holocene extinction and made it through the Telogene-Tularean extinction with relatively high diversity, radiating after each event. The Proximozoic has not been kind to them, however; environmental changes and competition from birds and dragons have led to the extinction of many bat lineages. 175 million years hence, the oceanic seabats are among the few that remain. Seabats like Halenycteris are the most aerial animals the planet has yet seen. They live their entire lives on the wing, and some individuals have never seen land in their lives. The young are born and raised in flight, being carried in a pouch until they are old enough to fly on their own. These bats have lost extensive tissues around the ears and nose in the name of streamlining, and have lightweight bones and a unique breathing system involving air sacs in the wings. Halenycteris grows up to five meters in wingspan, and soars the vast Pacific ocean dip-feeding for fish.

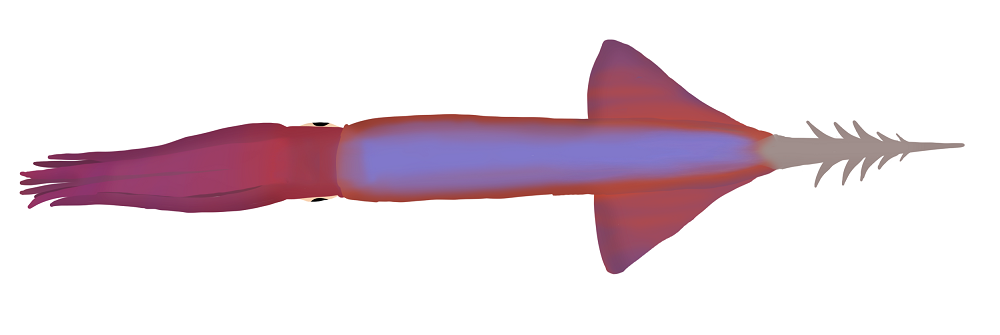

Jaculoteuthis purpureusDartsquids are so named because they bear a large “dart” at the posterior end of the mantle. This dart consists of a hard chitinous covering surrounding the only remaining portion of the internal shell. Dartsquids hunt by ramming themselves mantle-first into prey at high speed, impaling it with the sharp dart. Without the constraint of a shell running the length of the body, dartsquids are quite flexible, free to curl around and eat prey or clean the dart. Dartsquids evolved near the end of the Cenozoic, around 50 million years hence. In the wake of the Telogene-Tularean extinction, the clade radiated and became a major guild of oceanic predators. 175 million years hence, they have remained more or less unchanged. Jaculoteuthis grows up to a meter in total length, though species range in size from approximately a dozen centimeters to over two meters.

Titanophisuchus leviathanOne lineage of aquatic Proximozoic crocodilians is the Ophisuchia, which have particularly long, streamlined bodies and are fast swimmers. The sea orm is by far the largest, with the longest specimens exceeding 15 meters. The front of the sea orm’s snout is toothless and covered by hardened keratin. It has a varied diet, which depending on the individual can include cephalopods, fish, cnidarians, crustaceans, and large benthic worms. Sea orms can be found globally, except for in the narrowing Atlantic Ocean.

Parasiteuthis callowayiThe cookiecutter squid is a medium-sized pelagic squid species common in the Pacific Ocean 175 million years in the future. It its noteworthy for its habit of attaching itself to larger animals such as mermice, sea orms, or Cetornis. When a potential host animal is sighted, it will rapidly shoot its tentacles towards it. These tentacles are deceptively strong, tipped with chitinous hooks, and function similarly to a grappling hook. If the squid manages to anchor itself onto the host, it will retract the tentacles and grip to the host’s surface with its other arms, the inner surfaces of which are also lined with hooks. Once attached, it will use its powerful beak to excise chunks of flesh. An individual may remove many pieces of flesh from the same host, leaving extensive wounds. |

| ← Mediterranean Mountains, 135 myh | Siberia, 200 myh → |